Partition and Independence of India and Pakistan

The end of British rule in India was fraught with uncertainty and discord. The people of British India were in favour of independence. However, they were divided on their visions of independence. The Indian National Congress that led the popular nationalist movement favoured an undivided India, whilst the All-India Muslim League leaned towards the creation of a separate Muslim-majority state for Indian Muslims. Communal violence between Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims had increased towards the end of British rule. This strengthened the cause for a two-state solution. The newly elected Labour government in Britain was also keen to leave India after the Second World War. Britain was heavily economically indebted due to the costs of war and the British public were in general support of Indian independence. The deteriorating communal relations in India, British eagerness to depart from India, and the lack of trust between the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League saw the partition of British India into two new states in August 1947.

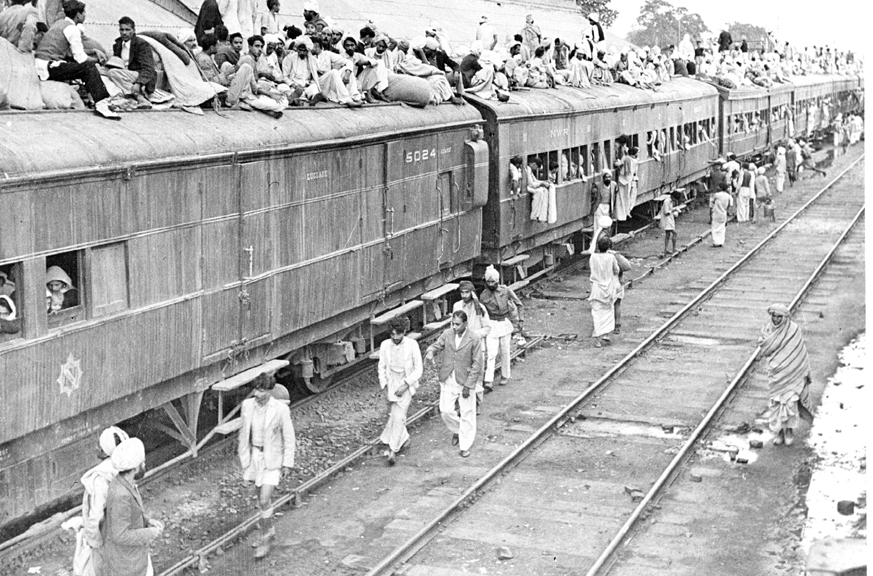

The partition of British India on 14th August 1947 to create the nations of the Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan was one of the major events of the 20th century. It concluded the end of 200 years of British colonial rule and realised the political ambitions of tens of millions of people of the Subcontinent. However, the price of reaching a political settlement between Britain and Indian representatives was a transfer of populations on a scale that had seldom been seen in modern history. Overnight, Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs that had lived side by side for centuries were compelled to abandon their ancestral lands and seek new homes in either Muslim-majority Pakistan or Hindu-majority India.

Partition was an emphatic response to a complex history. Initially, Europeans were met with one of the most powerful and wealthy political powers in the world in the form of the Mughal Empire when entering into Indian Ocean trade in the 16th century. However, regional challenges to Mughal power and European imperial rivalries led to political fragmentation on the Subcontinent by the mid-18th century. Emerging regional ‘successor states’ created a complex political tapestry which was made up of small chieftainships, sub-regional monarchic states, and large regional empires. The leadership of these various political formations varied in their religion, caste, and ethnicity. The armies of European trading companies and European states were often involved in the political contests between Indian powers as a way of furthering their own trading and imperial interests. It was in this political climate that Britain was able to transform from a trading power to a colonial power from the mid-18th century.

Over the course of the 18th and 19th century, The East India Company was able to defeat all the major successor states and achieve an unassailable position as the paramount military power in India. The Company had effectively extinguished the long pattern of Central and West Asian political domination of northern India. However, British political ascendency was not a straightforward process. British colonialism was characterised by challenges to its power as well as collaboration and allyship. As the British colonial state developed and centralised its power, it sought to pacify challenges to its authority through divide and rule policies and a calculated use of violence. In the long-run, Britain could not maintain its control over India without making political concessions of greater involvement of Indians in the affairs of the colonial state. This saw a succession of major reforms including the Indian Councils Act of 1909, the Government of India Act of 1919, and the Government of India Act of 1935.

These various constitutional changes were heading in the direction of mass elections and representative democracy. This necessitated the emergence of sectional political organisation based on race, religion, caste, and class. Various British policies had served to divide rather than unite Indian society. These included military recruitment policy which divided Indian society between ‘martial’ and ‘non-martial’ races and introduction of separate electorates for minorities. The complex demography of India and the push for mass involvement in politics heightened religious consciousness and the sense that the interests of Hindus and Muslims were incompatible. This led to calls for the safeguarding of minority interests from the early 20th century. These two forces, the push for democracy and the safeguarding of minority interests, informed the many forms of popular nationalism in India.

There was an irrepressible march towards Indian independence after the First World War. The Indian National Congress (INC), which started off as a mouthpiece for the small English-educated Indian elite in the late 19th century, became a populist voice for Indian indepedence by the 1920s. Britain’s relationship with its colonies went through major change during the inter-war years. Greater political autonomy of the colonies was seen as inevitable and even desirable amongst liberal imperialists. Britain’s white-settler colonies were pushing for dominion status and such developments were met with Indian calls for political reform too. The major contributions made by Britain’s empire during the First World War furthered the cause for a devolution of powers. However, Britain-India relations were damaged by the continuation of war-time restrictions on civil liberties and the use of lethal force against incidents of social unrest.

The British response to the worsening social condition in India, which was partly a result of the economic impact of the war, radicalised Indian society and politics to a point of no return. Anti-British sentiment was running high in the Punjab after the war. The region was of strategic importance to Britain due to it being the north-western extremity of British India bordering Afghanistan and also being the primary province of military recruitment in India. A state of martial law was declared by the Governor of Punjab which restricted public gatherings. The British fear of rebellion in the Punjab ultimately resulted in the infamous Jallianwala Bagh Massacre also known as the Amritsar Massacre. The massacre was the great turning point of the Indian independence movement. It led to the Non-Cooperation Movement, that had it not been called off by Gandhi in 1922 after the Chauri Chaura incident, may have delivered Indian independence before the Second World War.

The emergence of party politics in India in the early 20th century was linked to inter-communal(religious) tension and violence. Religious enmity in India has a long and complex history. It was informed by medieval and early-modern contests for power centred on north India. They were also a result of the emergence of the British colonial state and its differential impact on Indian society along the lines of religion. Constitutional reforms resulting in mass participation in politics by the early 20th century coupled with socio-economic disparities between religious groups heightened a sense of religious difference. The imperative to secure minority interests became more pressing in the context of Hindu-majoritarianism which sought to provide an alternative to the secular nationalism of the Indian National Congress and a response to the All-India Muslim League (AIML) which was formed in 1906.

What initially began as a call for safeguards for minorities in a democratising India evolved into a call for a separate Muslim state for Indian Muslims by 1940. The position of the All-India Muslim League was informed by increasing communal violence as well as the breakdown in dialogue between the INC and the AIML. The INC considered itself the voice of all Indians and was increasingly unwilling to entertain the prospect of a delay in Britain’s departure from India. The AIML contested the INC’s claim that it represented all of Indian society including Muslims. Britain was keen to exploit tensions between the two parties, particularly during the Second World War. Britain had unilaterally declared that India was at a state of war with the Axis powers without consulting Indian politicians. This led INC politicians to withdraw from government and effectively disrupt the functioning of the political system. In these circumstances, Britain sought closer ties to the AIML and promised the party an enhanced role in post-war discussions on Indian political reforms. The elevated status of the AIML, which belied its weak showing in the elections of 1936-37, would prove extremely significant for post-war developments. The AIML had established legitimacy as a representative of Muslim interests in the eyes of the British and later it secured the backing of Indian Muslims in the elections of 1945-6. The end of the war, differences between the INC and AIML, and Britain’s decision to transfer power to Indian political representatives set the stage for Indian and Pakistani independence.

Britain was economically crippled by the Second World War. It was heavily economically indebted and moreover was spending more on maintaining its Indian empire than it was deriving any economic benefit from it. Calls for Indian independence were reaching a crescendo whilst the aura of British invincibility ‘east of Suez’ was severely mauled by major Japanese advances in South-East Asia during the war. Perhaps more worryingly, Indian POWs under Subash Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army (INA) had directly engaged British Indian forces. Although the INA was ultimately defeated in the late stages of the war, there was a huge outpouring of sympathy for INA troops standing trial for treason. Britain’s Indian empire was built on the strength and loyalty of the Indian army. The potential politicisation of the army and the prospect of a repeat of the Indian mutiny of 1857 given Britain’s weakened position after the war was something that had to be avoided at all costs. These various factors resulted in a British plan to quickly withdraw from India whilst ensuring that amicable relations were secured with Indian political representatives in what was to become a new age of global contest for power and influence led by the United States and the Soviet Union.

Plans for the partition of India were hastily drawn up by Cyril Radcliffe who had little understanding of the complex demography of India and moreover had not been to India prior to his appointment as head of the Boundary Commission. Radcliffe arrived in Delhi on 8th July 1947 and a month later had produced a map with proposed borders for the new states. Radcliffe spent little time in the regions that would be affected by his border and primarily relied on outdated census data that broke down populations according to religion.

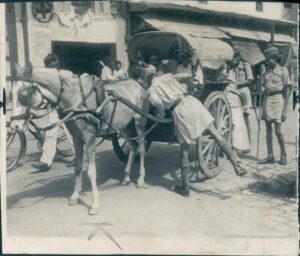

Ultimately, India and Pakistan’s independence was bittersweet. As the new nations awoke to freedom on the stroke of the midnight hour millions of people were forced to abandon their homes or were caught up in communal violence. The transfer of populations between the two nations was poorly managed and military authorities were unable to contain the ensuing violence that accompanied partition

Large parts of the Punjab, Sindh, the United Provinces (Uttar Pradesh), and Bengal witnessed demographic change. Many Muslims in Delhi and the surrounding region migrated to Karachi whilst Hindus and Sikhs of what became Pakistani Punjab often made the opposite journey settling in towns and cities in which Muslims had left for Pakistan.

Check out: The 1947 Partition Archive

Check out: India – A People Partitioned – Oral Archive

Share this Article

Our Funders