The Act of 1919 introduced elected representatives to the provincial councils and paved the way for later reforms that would grant Indians a greater say in their own affairs.

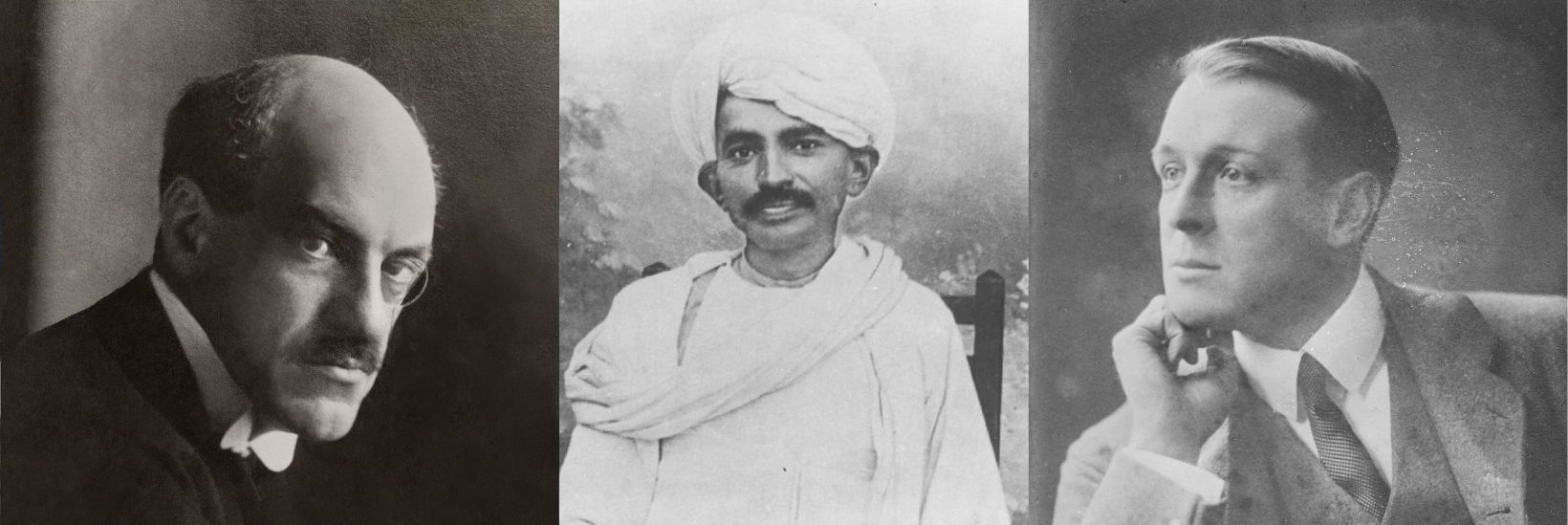

Mohandas Gandhi’s thoughts on the reforms were published in his journal the Navajivan:

“By the time this article appears in print, the Reforms Bill will have become or will be about to become law. What shall we do with these reforms? The answer to this question depends on the kind of reforms they are. If we measure them with the yardstick of the Congress-League Scheme, we ought to reject them; if we accept the resolutions passed at the last Congress, we shall find an ocean of difference between them and the reforms. What do we mean by “rejecting” the reforms? “Rejecting” them means refusing to work them. Not working them means abstaining from voting, from enlisting ourselves as voters or standing for election as members. No one is ready for such rejection, nor have we made any efforts towards that end. The deputations which went to England gave no indications to that effect. It must also be admitted that the nation is not yet ready for such rejection; it has not had the required political education. Whenever something is disapproved by us so utterly that its acceptance will kill the soul, then we are entitled, we owe it as a duty, to reject that thing; the idea that it is only by such rejection that we can raise ourselves in the shortest possible time has not yet taken root in us.

According to the canon ‘the doubter goes to destruction,’ we shall not be ready for great sacrifices so long as we doubt this idea. We are able to experiment thus only in small matters. By “small” we mean such matters as those in which sacrifice brings immediate result and involves no risk of serious danger. If we reject the reforms, it seems more likely that we shall get no immediate benefit. Hence, it will not be advisable for us to reject them.

We may certainly criticise the reforms, but the criticism should be moderate and intended only as an expression of our disappointment. We can and must say that we will struggle for more. But the more important thing is to find out how we can make the best use of these reforms and use them so. We must acknowledge here that the Bill introduced in the House of Commons has been amended and important rights have been conceded to us. At one time we had very little hope of securing them. It even used to be said that the Reforms Bill would not be passed at all at present. Instead, the Bill will now pass with some welcome amendments. We may derive what comfort we can from these things. There is no doubt that the real credit for these improvements goes to Mr. Montagu. That the Reforms Bill will pass in no more than a few days now should also be credited to Mr. Montagu’s account. After studying the reforms, the nation should try to send honest and competent representatives to the legislatures.

To the extent that the representatives care little for honour, for position and consequential material benefits, to the extent that the service of the people is their chief aim, the reforms will be better used and we shall be qualified the sooner for full responsibility and succeed in securing it. What about the Rowlatt Act? What about the Punjab? We had the best remedy for these, if we could have rejected the reforms. Now the only course for us is to make good use of the new councils for securing justice in both these matters. The Rowlatt Act ought to be repealed and agitation to that end can be carried on in the Legislative Assembly. If we fail, our weapon is ever ready with us. The same about the Punjab. It has yet to get justice and the place where we can secure this, too, is the Legislative Assembly. In both these matters, the new representatives and the reforms will be on their trial.”

Source: Navajivan, 14 December 1919, cited in The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. XVI, (The Publications Division: New Delhi, 1965), p. 341-42 REFORMS

Lionel Curtis, an influential advocate of liberal imperial reform stated the following on the merits of greater freedom for Indians in 1917:

‘Our whole race has outgrown the merely national State, and as surely as day follows night or night the day, will pass either to a Commonwealth of nations or else to an empire of slaves. And the issue of these agonies rests with us, in which word I include yourselves. Your own freedom is at stake, the freedom not merely of this Commonwealth, but that of the World. With us it rests to destroy it by our own ignorance and divisions, or else to renew and enlarge it by such unity in counsel and action as profounder knowledge, a fuller understanding of and greater affection for each other alone can bring. Let us leave this talk of conspiracies and think more of each other and less of ourselves. And this I would urge on my own countrymen, no less than on my fellow citizens in India. With inveterate foes thundering at our gates it is scarcely the time for, the nations of this Commonwealth to harbour unworthy Suspicions of each other. And when peace returns and the time has come to repair its breaches, to widen its walls and extend the freedom they guard within, let us then remember the words in which Parliament from of old has been wont to address the King ‘that His Majesty may ever be pleased to put the best construction on all their words and acts.’ Now, and also in the time to come, let us deal with each other in the spirit of that prayer.”

Extract from Lionel Curtis, Letter to the People of India (MacMillan and Co. Limited: Bombay, 1917)